news

Celebrating The First Birthday Of The Spamhaus BGPf

Introduction

In June 2012, Spamhaus launched the Spamhaus BGP feed (BGPf), a new service designed to protect organizations, network owners and network providers from malicious traffic. A year has passed since the Spamhaus BGPf was released and we would like to share some experiences that we at Spamhaus as well as the BGPf users have had in that time.

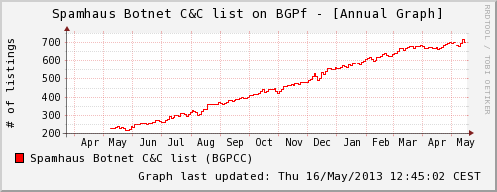

The Spamhaus Botnet C&C (BGPCC) is designed to protect networks and their users from botnet traffic. It can be used to block traffic from/to servers on the internet that are operated by cybercriminals and used to control infected computers (bots) or exfiltrate data. In the first year of operating BGPCC, Spamhaus has identified more than 5,700 botnet controllers that met the listing criteria for the BGPCC. Currently, the BGPCC contains more than 670 single IP addresses that are considered to be botnet controllers:

Below is a list of the malware families associated with the number of command and control servers identified by Spamhaus and which has been listed on BGPf in the past year. In addition, we have included 323 IP addresses associated with the Blackhole Exploit Kit (BHE) that is being widely used to distribute malware.

| Malware | # of C&Cs | Note |

|---|---|---|

| ZeuS | 848 | eBanking Trojan |

| Citadel | 691 | eBanking Trojan |

| Torpig | 506 | eBanking Trojan |

| SpyEye | 324 | eBanking Trojan |

| DDoS bots | 297 | Various DDoS C&Cs associated with DirtJumper, BlackEnergy, etc. |

| BankPatch | 200 | eBanking Trojan |

| Dorkbot | 156 | Worm |

| Ransomware | 103 | Various Ransomware families |

| Spambot C&Cs | 80 | Various Spambot families (Cutwail, Spamnost, Grum, etc.) |

| Pony | 69 | Dropper |

| Feodo | 63 | eBanking Trojan |

| Carberp | 60 | eBanking Trojan |

| URLzone | 35 | eBanking Trojan |

| Virut | 31 | Worm |

| Necurs | 25 | Backdoor |

| Hermes | 14 | eBanking Trojan |

| Other threats | 952 | Other malware families |

| generic | 947 | C&Cs were the associated malware could not be identified |

Note: The list above does not include the botnet C&Cs which were hosted on hijacked webservers/websites or fast flux botnets.

Spamhaus does more than just listing bad IP addresses on BGPCC: once a botnet controller has been identified, an abuse report is sent to the responsible Internet Service Provider (ISP). In this fashion, Spamhaus can ensure that the ISP is able to take appropriate action to prevent further crimes from being committed. Since The Spamhaus Project was founded in 1998, Spamhaus has put a lot of effort into working with ISPs and Web Hosting Providers to find appropriate solutions for their abuse problems. We are glad to announce that 90% of all reported botnet controllers were shut down after Spamhaus reported them to the responsible ISPs. In the remaining 10% of cases, the botnet C&C is still active, or the ISP failed to notify Spamhaus about the problem resolution.

The Spamhaus extended DROP list (EDROP "The Spamhaus Don't Route Or Peer Lists ")), which was also launched in June 2012, has identified 56 networks that meet the listing criteria for EDROP. At the moment, there are 23 active listings on EDROP.

In addition, we have identified another 50 networks that meet the listing criteria for DROP, which shares the same listing policy as EDROP, but with the slight difference that only contains direct allocations, versus EDROP which lists only suballocations.

Spamhaus takes pride in providing reliable services to the community and to Spamhaus users. In the past year we had some great experiences which we would like to share with you.

Mitigating spam emission at the ISP level

In November 2012, we performed a real world test in cooperation with a large ISP in central Europe that provides services to more than 1.8 Million customers (mostly DSL / broadband customers). We provided a tiny subset of BGPCC data, which only contained botnet controllers associated with the Cutwail spam botnet. Using real time data from Spamhaus XBL about bot infected machines, Spamhaus was able to accurately identify computers infected with the Cutwail spam bot. Then, all the Cutwail botnet controllers that were listed on BGPCC were blocked for a period of 14-days by the ISP. Spamhaus measured the number of spam emitting IPs associated with Cutwail before, during, and after the black-holing. Below is a chart that illustrates what was observed during this test:

On November 5 2012, as the ISP started to blackhole the IP addresses of the Cutwail command & control servers (C&Cs), Spamhaus saw a notable decrease in the number of spam emitting IPs from the participating ISP. The slow but continual decline in spamming IPs can be explained by the fact that it took some time for all the Cutwail infected bots to finish their current assigned tasks. As soon as they did so, the bots tried to "phone home" to receive new instructions. These attempts failed because all the Cutwail C&Cs had been blackholed by the ISP. The result was that the infected machines were unable to send out new spam emails. The decrease of detected Cutwail IPs in the ISP's network lasted for 2-weeks. When the IPs were unblocked on November 19th 2012, Spamhaus XBL saw a massive increase in actively spamming IPs that were associated with the Cutwail spambot at the ISP.

This real world test showed how effective blocking malicious traffic at the ISP level is. It not only helps to protect customers and internet users from cyberthreats but also helps to reduce the workload created by such threats (eg. in this case less work for the abuse desks due to lower spam emission). The reputation of a network can also improve in the view of others.

BGPf Case Study at Schibsted

In mid 2012, we made a BGPf case study in a production environment. Schibsted IT, a subsidiary of one of the biggest media groups in Norway subscribed to the Spamhaus BGPf. They decided to implement all three feeds (DROP, EDROP and BGPCC). Instead of just blocking bad traffic, Schibsted decided to "sinkhole" the advertised IP addresses by redirecting the traffic to a server that is under their control. In this manner they were able, on a daily basis, to identify several infected computers within their network.

The whole case study regarding Schibsted IT can be found here:

- Case Study - Using Spamhaus BGP feed in a Production Environment - HTML version at securityZONES website

- Spamhaus BGPf Case Study at Schibsted IT (full 256KB PDF)

References

Spamhaus Releases BGP feed (BGPf) and Botnet C&C list (BGPCC)

[Spam botnets: The fall of Grum and the rise of Festi

Spamhaus BGP feed (BGPf)](http://www.spamhaus.org/news/article/685/spam-botnets-the-fall-of-grum-and-the-rise-of-festi)